Most developed economies have mature approaches to flood management. For example, the European Floods Directive[1] means that common tasks such as flood mapping, the construction and operation of flood management measures and warning systems will be broadly similar. The impacts of climate change on flood risk will have been assessed. Land use planning, also known as zoning, helps development to be resilient and steers it away from areas at risk of flooding. Despite all this there will be times where flood managers can only reduce the risk of occurrence of flooding. In some cases, the risks will be too high and require managed realignment.

That is the planned movement of people, infrastructure and settlements away from risk.

One of the additional means a country can adopt is to socialise risk by using insurance. Broadly speaking OECD nations have flood insurance schemes which are public, private or hybrid, all have strengths and weaknesses. Common perceptions are that private systems are more efficient but can exacerbate deprivation by trapping poorer communities in uninsurable homes. On the other hand, state systems can be slow to settle claims and, because of their generosity, distort real estate markets or encourage irrational[2] behaviours. For example, premiums might reflect risk to a lesser degree encouraging ‘free riders’ with few incentives to reduce their personal risk. Conversely state schemes are more likely to take advantage of beneficial feedback loops through enforcement of zoning and building codes for risk reduction, or by requiring property owners to receive warnings as a condition of insurance.

Many nations insurance schemes have been in place for decades. However, as climate change bites, they become increasingly stressed. In the UK flood insurance was offered to all policy holders. Then property flooding from the early 2000s became increasingly common and costly for insurers. The level of claims became so high that homeowners found that premiums and deductibles made the cost of living in flood prone areas burdensome. In the UK lenders require homeowners to arrange cover, but for those at high risk, supply of insurance was limited to one or two carriers and costs were high and rising. To protect the real estate market the government had to intervene, eventually setting up Flood Re, a state backed reinsurer of last resort. This has been a success, stabilising the market for now, but how long can this be sustained?

The flood risk landscape is changing. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) heavy rainfall[3] that causes flooding has likely increased and will continue to do so, 1 in 100 year river floods in the UK will have peak flows 15-30% higher by 2050[4]. The IPCC state that Global Mean Sea Level will rise of between 0.43 m (0.29–0.59 m, likely range; RCP2.6) and 0.84 m (0.61–1.10 m, likely range; RCP8.5) by 2100 (medium confidence) relative to 1986–2005[5]. Outlier scenarios indicate greater rates of Sea Level Rise (SLR) of 1.1m or more by 2100 cannot be dismissed[6]. Analysis in the UK suggests that 120,000 to 160,000 properties might be impacted by managed realignment policies by 2050[7].

1 in 100 year river floods in the UK will have peak flows 15-30% higher by 2050 - IPCC

0.43 m (0.29–0.59 m, likely range; RCP2.6) and 0.84 m (0.61–1.10 m, likely range; RCP8.5) by 2100 (medium confidence) - Global Mean Sea Level rise relative to 1986–2005 - IPCC

120,000 to 160,000 properties might be impacted by managed realignment policies by 2050 – Science Direct

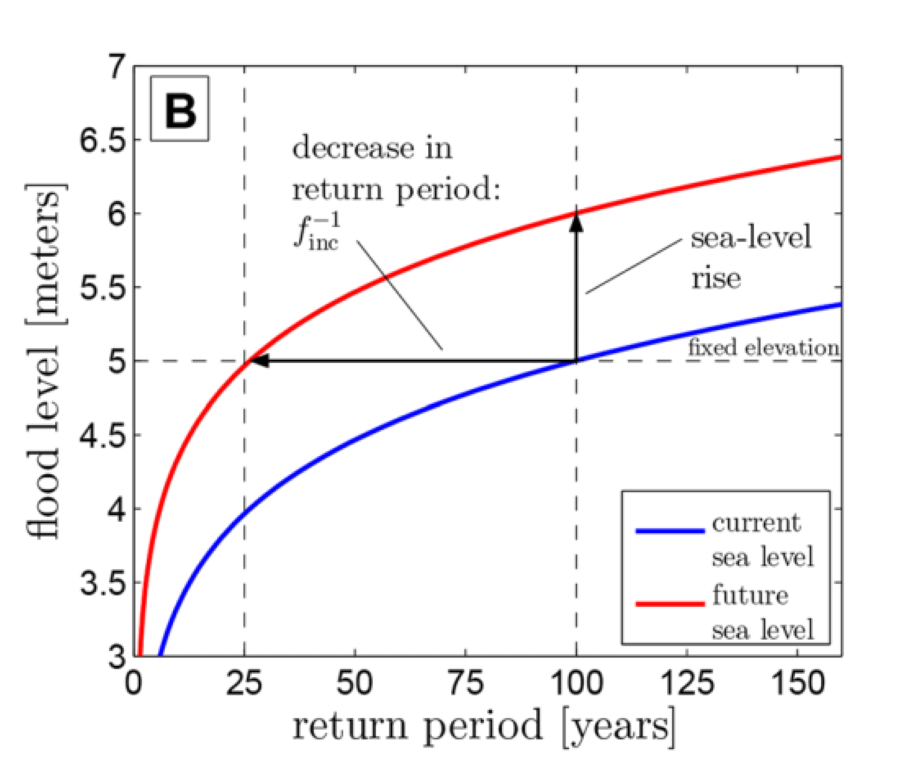

SLR will affect countries in many ways, two will be considered here. Without modifications to sea defences SLR will increase the frequency and severity of flooding. This is clear from analysis of static water levels. However, increases in storminess will compound the risk posed by higher sea levels to make coastlines more susceptible to flooding. The rate of increase of coastal flooding may go up by two or three orders of magnitude by 2100[8], [9]. Furthermore, SLR will continue for centuries, the last time the CO2 level was as high as it is now, substantial portions of Greenland were ice free, this has grave implications for the future.

Studies suggest that natural hazards are increasingly discounting asset values of property[11], [12]. Development of a new system with a greater emphasis on risk offers the potential to reduce risks to the state and banking sectors. At the same time, it might encourage risk reduction behaviours in those exposed to floods and storms.

Considering other schemes is useful, but they are a product of the social and institutional infrastructure of the nations in question. It is useful to study them for lessons learned, however, transplanting a system wholesale to a new country is unlikely to succeed.

So, to imagine a perfect system; no insurance gap, affordable and fair risk based pricing. Near comprehensive cover with incentivisation to risk reduction behaviours by the state and property owners. This may be possible in a stationary climate, but unlikely to be stable in the face of climate drivers such as increased storminess and rising sea levels. In a system where risk is increasing, risk reduction behaviours will be on a continuum between preparedness and resilience through to an acceptance that some places will have to be relinquished to the sea at some point in the future. Maybe a dynamic insurance system is the answer.

Introducing a new scheme is a transition which needs to be carefully considered, just talking about it can set horses running. It is a given that any scheme will involve financial modelling to ensure that pricing works for the insured and insurer. Further thought needs to be directed toward the likely rate of uptake, the degree to which cross subsidisation is acceptable and the level of cover offered.

These are the ‘normal’ actuarial things which are calculated when setting up an insurance programme. But it is worth looking at the plan from a different perspective. Perhaps the first question which should be asked is how long should a new scheme last? Some nations have introduced new flood insurance schemes, these may have a defined end date[13] or a fixed term from launch[14]. Given an upward trend in risk and accelerating rates of SLR, a system has to be resilient to change or buy time for a new set of flood management and financial policies to be prepared. This decision will likely be led by economics, but the earlier a system is agreed and the longer the lead time, the easier it will be for societies to prepare and adapt.

Staying with the passage of time, will the onset of increased risk be swift as hinterlands are reclaimed by the sea in dramatic steps? Or will the number of properties gradually increase in a linear manner? The more time there is before substantive change, the more flexibility there is to communicate and ensure fairer outcomes. There is evidence to suggest that some areas of the world are particularly vulnerable to the effects of SLR in the near term[15], particularly where vertical land movement accelerates relative sea level change. The designer will need to weigh up these elements.

Given an upward trend in risk…a system has to be resilient to change or buy time for a new set of flood management and financial policies…

…need to balance present day risk mitigation against long term deterioration in property value driven by…increased …windstorms and flooding.

Insurance is there to socialise risk, but not to distort other markets. There is a need to balance present day risk mitigation against long term deterioration in property value driven by the increased frequency of windstorms and flooding. While the moral hazard of free riders whose policy pricing is not risk based is obvious, a designer should not transfer risk or unsolved problems to future generations.

Coastal flood risk management strategies use adaptive planning techniques. As flood risk increases over time a range of different interventions can be brought forward, think of it like a golf bag of clubs or actions. There is a disparity between annually renewed insurance policies and the duration of mortgages, and the infrastructure required to mitigate flood risk. Financial products including insurance could be developed to align themselves to adaptive planning. Preannounced loading of policies, tapering of deductibles and loan to value ratios could be introduced according to the rate of change of risk and parallel coastal policy would send strong signals. In this instance scheme administrators would need to plan for the central, most likely changes, but stress test to the worst case. Given the long-term nature of the problem of SLR it might be difficult to optimise a solution for the present day that will be practical in 2150.

Reward for resilience at a property level might be achieved either through preflood loans or post flood build back better schemes. Like a home Energy Performance Certificate (Energy Performance of Buildings Directive - 2010/31/EU) a property might be awarded a Flood Performance Certificate[16] (FPC). Under consideration in the UK, an FPC would provide a report on flood risk according to the latest mapping. It would reassure purchasers that, at a property level, measures were installed and tested according to British Standard BS 851188. However, this will not manage medium to long term change brought about by big drivers like sea level rise.

By bundling all perils into one policy but setting the premiums according to risk will widen the pool and make the scheme more resilient.

By bundling all perils into one policy but setting the premiums according to risk will widen the pool and make the scheme more resilient. Some might argue they are not at risk of flooding, but all will have some exposure to wind, fire or subsidence. Most though are exposed to the secondary effects of weather damage to their communities or infrastructure, so will gain measurable benefits. Risk based pricing itself sends a powerful signal to property owners as to the need for action. In smaller countries where a single large event could be too big for local markets to handle, it will be of benefit to seek opportunities to pool through wider reinsurance markets.

Aligning and structuring all components… has the potential to be transformational and can reduce… following generations inheriting a mess

Developing a new insurance scheme for a country is only a part of the problem that states face when managing flood risk. New engineering infrastructure is part of the answer to more resilient societies. Aligning and structuring all components of the system has the potential to be transformational and can reduce the likelihood of following generations inheriting a mess.

WTW has broad and deep experience in creating insurance risk pools, (re)insurance modelling, climate and disaster risk finance and policy in insurance and forecast-based finance, risk analytics modelling and index design for climate hazards, including flood. More than ever, a close link to the science and engineering community is needed for effective flood risk management. This was clear to see at the recent Global Flood Partnership annual conference in Singapore, convened by our long-term partner the National University of Singapore. The combination of science with finance and national flood management policy can suggest a roadmap to optimise the design of a potential new flood insurance scheme, taking into account the ‘factors to consider’ mentioned in this note.