“Follow the money”. The counsel attributed to Watergate reporter Bob Woodward’s FBI source in the screen version of All the President’s Men should be heeded by anyone seeking to understand the Government’s policy on expanding automatic enrolment into workplace pensions.

In its Automatic Enrolment Review, published in December 20171, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) proposed making everyone’s earnings pensionable from the first pound and lowering the age threshold for enrolment from 22 to 18. For affected individuals earning more than £520 per month, the proposed expansion of pensionable earnings would see £41.60 per month more going into their workplace pension. For basic rate taxpayers, half of this would effectively come from take-home pay2 – though the difference between take-home pay in a world where the change happens and one where it does not will be higher if employer pension costs put a brake on pay growth.

On 23 January, the pensions minister, Laura Trott, told the House of Commons that, “… we remain committed to implementing the 2017 reforms in the mid-2020s”3. Similarly, the Government’s response to a Work and Pensions Committee report, published on the same day, said: “We remain committed to the implementation of the 2017 Review ambitions in the mid-2020s”4.

If these words appeared to convey an unqualified commitment, following the money would disabuse you of that idea. The Office for Budget Responsibility’s latest forecasts5 extend to 2027-28, and it is hard to stretch the definition of “mid-2020s” beyond then. As the 2017 proposals would be expected to affect wages and Government revenues, the OBR must make an assumption about whether the changes happen within the forecast period, and it assumes they do not6. This reflects advice that HM Treasury gave the OBR shortly after the Review was published7, which has not been updated. The finance ministry’s stance is part of a long tradition of slowing down the implementation of policies in this area (for example, the Government originally said that the current minimum contribution rates would be phased in over three years from 20128, but this process did not complete until 2019).

Sure enough, when the Department for Work and Pensions published the outcome of its annual review of automatic enrolment earnings thresholds on 26 January, it confirmed that: “Government remains committed to this, subject to discussions with employers and other stakeholders on the right implementation approach, and finding ways to make these changes affordable”9. For the most part, these caveats echo those in the original 2017 Review paper. (So “we remain committed” appears to mean that the Government remains no more or less committed than it was to begin with.) On 7 February, the minister told MPs that she is “keen to set out a timeline” and will do so “as soon as I have collective agreement”10; that would include the Chancellor consenting to putting the fiscal cost on his Budget scorecard and the Government choosing to prioritise the necessary legislation as a use of Parliamentary time (either by introducing its own Bill or by supporting a backbench Bill that has its second reading on 17 March)11.

This is not to say that the changes will not happen on something like a mid-2020s timetable. Perhaps the Department for Work and Pensions will put this on the table during negotiations about the State Pension Age (where HM Treasury reportedly favours a faster increase than DWP) or about ideas such as allowing pension pots to be used for house deposits (which might be considered a vote winner by others in Government but has reportedly met resistance from within DWP in the past). Suppressing take-home pay in the next Parliament may also be less of a worry if ministers come to believe that they are unlikely to be in office at the time – though an incoming Government could always slow down the timetable it was bequeathed …

In the threshold review, the Government announced that the earnings trigger (£10,000 on an annual basis) and qualifying earnings band (£6,240 to £50,270) would be the same in 2023-24 as in 2022-23 and, indeed, 2021-22, rather than being adjusted to reflect changes in prices or earnings over the past year.

One consequence of this is that, for the first time, the earnings trigger will be above the full New State Pension (roughly £10,600 in 2023-24, after the Triple Lock delivers a 10.1% increase). Accordingly, some part-time workers will by default put money aside for a time when they would expect their income to be higher than it is today. This is not the nudge towards consumption smoothing that automatic enrolment was supposed to provide – though, in practice, many of these people will have partners working full-time and so can expect their household’s income to fall at the point of retirement. The gap between these numbers will widen over time if pension contribution limits remain frozen and State pensions Triple Locked.

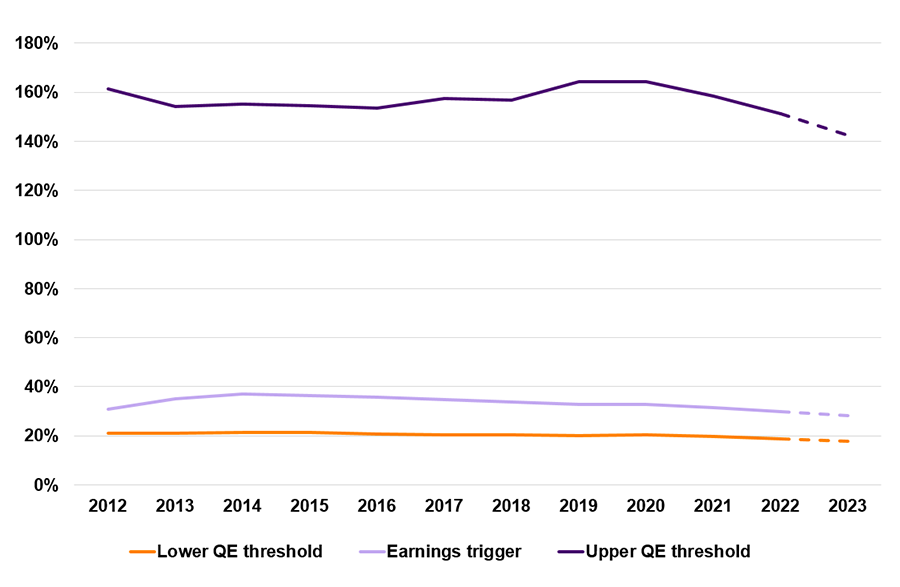

Continuing to align the top of the qualifying earnings band with the frozen National Insurance Upper Earnings Limit means that even below-inflation pay rises will make an increasing proportion of higher earners’ pay non-pensionable where their employer complies on the statutory minimum basis. This policy will therefore increase the value to these employees of many large employers having chosen to base contribution rates on full basic pay. In April 2020, the top of the qualifying earnings band was over 1.6 times full-time median earnings12. Three years later, that multiple is likely to be a little over 1.4 times, with the precise number of course depending on April 2023 earnings levels13. Meanwhile, the earnings trigger and lower qualifying earnings threshold have been trending down as a proportion of median full-time earnings (expanding the policy’s reach), but less sharply.

Earnings data is for April each year14; chart assumes 6% year-on-year growth in the year to April 2023; this is illustrative, not a WTW forecast.

8% of qualifying earnings is never more than 7% of all earnings: it can be this high for someone with earnings exactly at the Upper Earnings Limit, but will be a smaller percentage for everyone else – and the percentage gets smaller the further that earnings move away from the UEL, in either direction.

Although minimum contribution rates were not fully phased in until 2019, it may be worth noting that 8% of QE has become a lower proportion of gross earnings for higher earners (down from 5.6% in 2012 to roughly 5% in 2023 for someone on twice median earnings), and a higher proportion for lower earners (up from 4.6% to roughly 5.2% for someone on 50% of median full-time earnings). Lower earners will, of course, see a much bigger jump if and when making pension contributions start from the first pound means that 8% of qualifying earnings finally equals 8% of earnings.

1. Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum, DWP, December 2017.

2. Calculation assumes that the employer only pays the statutory minimum 3%, leaving the employee to pay 5%, and that employee contributions are not made via salary sacrifice.

3. Hansard: House of Commons debates, 23 January 2023, Column 750.

4. Government response to the Committee’s third report of the 2022-23 session: Saving for later life, submitted on 11 January 2023 and published on 23 January 2023.

5. Economic and Fiscal Outlook: November 2022, published 17 November 2022.

6. The OBR’s December 2022 Policy risks database, available on its data page, explains that: “Parliament requires that our forecasts only reflect current Government policy. As such, when the Government sets out ‘ambitions’ or ‘intentions’ we ask the Treasury to confirm whether they represent firm policy. We use that information to determine what should be reflected in our forecast. Where they are not yet firm policy, we note them as a source of risk to our central forecast. In the printed EFO document we update on risks that are particularly large, have changed materially over the past year, or are new. Here we provide the full list of specific policy risks to this forecast and changes from the previous update.” The 2017 proposals are categorised as a “remaining” risk.

7. In its March 2018 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, the OBR had said: “The Government has told us these remain policy ambitions so we have not included their effects in our economy or fiscal forecasts. Auto-enrolment in its present form is factored into our economy forecast as a wedge between total employee compensation and wages, while tax relief on the employee pension contributions features in our income tax forecast. These proposals would increase both adjustments.”

8. Security in retirement: towards a new pensions system, DWP White Paper, May 2006. These contribution rates had been proposed by the Pensions Commission in November 2005.

9. Review of the Automatic Enrolment Earnings Trigger and Qualifying Earnings Band for 2023-24: Supporting Analysis, DWP, January 2023.

10. Hansard: Westminster Hall, 7 February 2023, Column 267WH.

11. Primary legislation might not be needed to reduce the bottom of the qualifying earnings band to zero, but it would be needed to reduce the age threshold. The Pensions (Extension of Automatic Enrolment) Bill has not yet been printed. Based on its original sponsor’s speech at first reading, it would not commit the Government to a specific timetable for implementation, which could be specified in secondary legislation.

12. Earnings data from Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, Office for National Statistics, October 2022.

13. In this blog, calculations assume an illustrative 6% growth in median full-time earnings between April 2022 and April 2023. For context, whole economy average weekly earnings were 4.1% higher in November 2022 than in April 2022, but this number can diverge from the median earnings number used in the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings.

14. From the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings. Data from 2021 is based on different standard occupational classifications; we have not adjusted for this, but the effect is immaterial.